Ever since people invented trash, the sea has served as our favorite dump.Getting rid of garbage on land is hard work, and it involves burning and/or burial. Burning rubbish creates sick smelling smoke and leaves behind ash that still needs to be buried. Burying means digging up lots of dirt, and no matter how much dirt is dug, all landfills inevitably fill up.

But when a dump has an average depth of 2.3 miles and covers over 2/3 of Earth’s surface, running out of room is never an issue. Besides the unlimited storage space, deposing debris at sea is as easy as dropping it in the water. Waste that sinks is instantly gone, while the refuse that floats is soon swept away by winds and currents. So the ocean essentially takes out the trash for us.

For millennia, all the debris we tossed into the sea was made out of natural materials derived from plants, animals, or ores, and they were all subject to natural decay. Once in the water, paper-like products quickly disintegrate, while wood rots and metal rusts. Due to the solvent power of seawater, the ocean was able to dissolve our refuse almost as fast we dumped it in. So through most of human history, the net result of our waste stream into the sea was just a gradual accumulation of ocean trash over time.

|

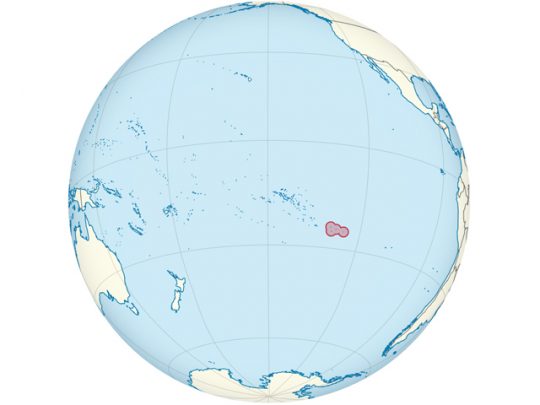

| Because Henderson Island is so remote, the uninhabited atoll has had very little direct human contact. Indirect human contact is a whole different story. Image: wikipedia |

Plastic replaced paper, wood, glass and metal in countless consumer items and packaging. Consequently, plastic also replaced much of that material in our landfills, and became a major component of the trash, aka litter, that never reaches the landfills. Much of that misplaced waste winds up in rivers, which in turn transport the trash down to the sea. That non-stop slurry of plastic pollution has been steadily flowing into our oceans for the last 60+ years.

|

| With an average of 557 pieces of trash per square yard, Henderson Island holds the world record for plastic debris density. Image: PNAS |

Once launched into the sea, the plastic debris is caught up in the ocean’s interconnected complex of currents. Those continuously shifting streams embedded in the sea range in size from small eddies driven by localized winds, to gigantic gyres powered by Earth’s own rotation. Like massive whirlpools pinwheeling in slow motion, the vast vortices circulate water around the periphery of entire oceans. Anything entrained in that circulation, (like Fukushima’s radioactive runoff), can be carried from one side to the sea to the other. Buoyant debris bobs along with the flow until it disintegrates, sinks or gets stuck on something stationary. Something like an island, for instance.

Henderson Island is a 14.4 square mile speck of land, located over 3,100 miles away from the closest continent and surrounded by millions of square miles of open ocean. The raised coral atoll’s nearest neighbors are the other three dots of dry land that collectively comprise the Pitcairn Islands, Britain’s last Overseas Territory in the Pacific. Just one of those four little islands, Pitcairn, is inhabited, and only with about 50 permanent residences, which makes the Pitcairn Islands the world’s least populous national jurisdiction.

|

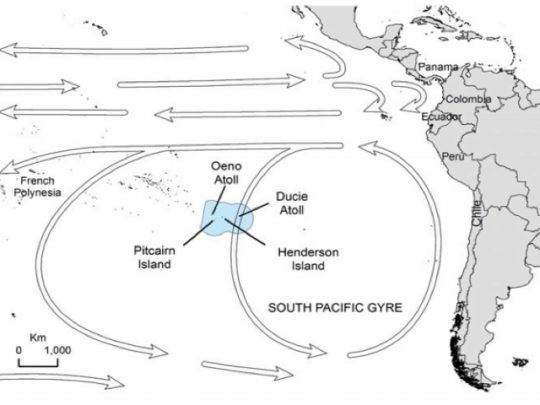

| The South Pacific Gyre gathers up sea debris then hauls the trash to Henderson Island. Image: PNAS |

Although Henderson doesn’t have any people, the diminutive island does have amazing biodiversity, with much of its flora and fauna found nowhere else on the planet. That’s why the atoll has been designated a World Heritage Site. Since the isolated island is so remote and untouched by human hand, it’s easy to picture the place as a pristine Pacific paradise. But while Henderson Island may lay beyond the reach of our grasp, it is well within the range of our garbage.

Waste-wise, Henderson Island has the misfortune of being situated in the midst of the South Pacific Gyre. That colossal, counter-clockwise circulation cell continuously collects the runoff refuse from dozens of different countries on three continents, with Chile, China and Japan contributing the greatest share of trash. The end result for Henderson’s beaches is an estimated 3,750 pieces of primarily plastic debris washing ashore each and every day, for an accumulative total of 37.7 million items either laying on or buried in the sand. All that trash concentrated in such a small space gives Henderson Island the highest density of plastic waste anywhere in the world.

|

| While some of the trash on Henderson Island comes in handy, most of the debris is hazardous to the inhabitant’s health. Image: PNAS |

While some continue to debate the charge of climate change, the proliferation of plastic pollution in the ocean seems to be a subject where we can reach a common consensus. No one denies that every piece of plastic in the sea was produced by people. At the very least that plastic litter is an eyesore, and at worst it is a lethal hazard to marine life. Reduction in plastic production is not the issue here, although that would be nice, this is simply about reducing the amount of plastic products which inadvertently enter the ocean. This is a cause we can all support and a goal everyone can help to achieve.

First, we ensure that we’re not part of the problem by making certain that all of our own waste winds up where it’s supposed to. Reuse and recycle all that you can and properly dispose of what pieces you can not. Next, we step up and contribute to the solution by taking responsibility for some rubbish that’s not even ours and putting that litter in its proper place too. When leaving the water, pick up and properly dispose of any plastic you see when crossing the beach. While the total amount of plastic debris in the sea may be overwhelmingly massive, every piece that we pick up is an immediate improvement and movement in the right direction. No matter how infinitesimal the actual effect of our individual efforts may be, the ocean still approves of such actions and we will be rewarded with more waves.

Tags :

#savetheocean

,

ocean

Subscribe by Email

Follow Updates Articles from This Site via Email

No Comments